Getting the basics down: compiler from scratch pt. 1

I like compilers, so I want to write one. Now, production quality compilers for name-brand languages, like GCC, weigh well into the millions of lines1. Even QuickJS and TCC (Tiny C Compiler), which aim to be small implementations of JavaScript and C respectively, come in at around 60k LOC each. Modern programming languages are fundamentally sophisticated beasts, and compilers are just inherently intricate, so its safe to say writing a real-world compiler is a significant undertaking.

Despite my best efforts, I haven't dissuaded myself, but I still don't have the patience (or probably skill) to write something like QuickJS or TCC. Instead, I want to write a compiler whose main purpose is fun, learning and exploration, and I want to document the process here. Hopefully anyone else writing a compiler — or really anyone else interested in compilers — will get something out of this series.

In this post, I'm going to go over the very basics of building a compiler in a pretty naive way, and I'll add some sophistication later. Actually, the "compiler" will be an AST interpreter for now, since I feel like thats a good stepping stone anyway.

What we'll implement

This project is contrived, so I'll be implementing a fairly contrived language. The language will be a very stripped down version of C, and since this is a toy project, I'll readily simplify the language to make the compiler work easier. I'm going to write the compiler in Java, because it's widely known, pretty easy to debug, and the garbage collector will come in handy. If I was trying to write a fast compiler, I definitely wouldn't use Java, but I'm not, so I will.

By the end of this post I'll have the following functionality up and running:

- Lexing and parsing source code into an AST.

- Some truly primitive validation of said AST.

- A pretty trivial interpreter that just walks the AST.

- Functions, parameters, variables, assignments, returns, integers, and nothing else, like calls or arithmetic.

We should end up with a project structure a bit like this:

Defining the AST classes

In compilers, there is the idea of an intermediate representation, which is whatever data structure the compiler uses to model the program.

Source code is a representation, and is modelled by the "data structure" java.lang.String.

This serves us poorly though.

Imagine writing a complex algorithm operating solely on the characters of the source code.

A good intermediate representation represents different things differently, represents similar things similarly, and doesn't represent anything we don't care about (like whitespace).

We seek structure, uniformity, and simplicity.

An abstract syntax tree, or AST, represents a program as tree of nodes, where each node corresponds to a piece of syntax, such as a function, statement, or expression.

For example, this program:

int main(int a) {

int b;

b = a;

return b;

}

Has this abstract syntax tree:

You can see how each piece of information in the program is structured based on "what belongs to what".

This intermediate representation will serve us quite well to begin with.

Note that there is some structure missing from the AST — maybe the return b node should have links to the declaration of b, or maybe a link to the type int.

There is also no link to the next thing to be executed, for example.

We can define "analysis passes" which will navigate the AST to fill in these missing details, but in more advanced cases, this strategy will be superseeded by better IRs, such as instruction based single static assignment forms2, or a sea of nodes representation3.

We will model our AST as an abstract class where base classes are the different types of nodes.

In the compiler, we will make extensive use of Java's new sealed classes, where a superclass lists out all possible subclasses in its declaration.

This will let us use pattern matching in switch statements, which will simply our code slightly.

This is essentially a glorified, safer way to do lots of instanceof checks, and we will use it in lieu of discriminated unions (like Rust's enum).

public abstract sealed class Ast permits BlockAst, ExprAst, FunctionAst,

IdentAst, ProgramAst, StmtAst, TyAst, VarDeclAst {

// An AST has a parent node, unless it is the root `ProgramAst`

private Ast parent;

// An AST has zero or more children, all of which are also AST nodes

public abstract List<? extends Ast> getChildren();

// Utility to search down the AST

public <T extends Ast> T findDescendant(Class<T> cls) {

// ...

}

// Utility to search up the AST

public <T extends Ast> T findAncestor(Class<T> cls) {

// ...

}

}

I've also defined ExprAst (expressions), StmtAst (statements), and TyAst (types) as abstract subclasses of Ast.

Since so many pieces of syntax fall into these categories, its nice to specify them upfront.

This is also a good point to mention that I will leave out a lot of code for brevity, such as getters and setters.

As such, I won't list out all the code for every AST node, but FunctionAst is fairly illustrative:

public final class FunctionAst extends Ast {

private IdentAst name;

// VarDecl means variable declaration

private List<VarDeclAst> params;

private TyAst returnTy;

private BlockAst body;

public FunctionAst(IdentAst name, List<VarDeclAst> params,

TyAst returnTy, BlockAst body) {

this.name = name;

this.params = new ArrayList<>(params);

this.returnTy = returnTy;

this.body = body;

}

@Override

public List<? extends Ast> getChildren() {

var results = new ArrayList<Ast>();

results.add(name);

results.addAll(params);

results.add(returnTy);

results.add(body);

return results;

}

}

Note how we can access the children of a function in a hetrogenous way, e.g. through the params field, but can also access its children in a homogenous way, through the getChildren method.

These are both convenient at different times.

One issue with this design is that we can't, and don't, set parent in the constructor.

This would be a chicken and egg problem, since we pass children into most AST constructors.

Instead, we can use the assignParents utility function to make sure the parent field is set correctly for the whole tree.

We will call this once after we finish building an AST.

public abstract sealed class Ast

permits /* ... */ {

// ...

public void assignParents() {

for (var child : getChildren()) {

child.setParent(this);

child.assignParents();

}

}

}

We will eventually have quite a lot of AST classes, but I've put the ones we have now below. Black represents concrete classes and composition, blue represents abstract classes and inheritance:

Lexing and parsing

Parsing is the process of turning our source code (as a string), into an AST. Since hand-written parsers tend to be very verbose, there are parser generators which provide a terse, domain specific language from which parsers can be generated. I've actually written a (fairly bad) parser generator, but I'm going to go firmly with rolling my own, for a few reasons. First and foremost, I've called this article "compiler from scratch" so I've sort of already boxed myself into that decision… In seriousness, I think parsers can be interesting, even if tedious. Parser generators also tend to suck — it's easy to hit a wall with them, and often the error reporting and recovery is subpar and not very customizable. Finally, despite parser generators purporting to simplify things, they also add a lot of complexity in learning the tool and integrating it into the build.

Parsing is generally regarded as the "easy" part when writing a compiler, but it is actually quite a rabbit hole with a lot of literature. Parsers can usually be classified as either top-down or bottom-up. I won't go into depth, but anything written by hand will usually be top-down, and most popular programming languages use a hand-written top-down parser since that enables the best error messages4.

The phrase "hand-written top-down" parser is essentially synonymous with recursive descent parsing, and indeed I'll be writing a recursive descent parser. Despite sounding a scary, recursive descent just means each piece of syntax has its own function, and these functions call eachother (maybe recursively) to recognise more complex syntax.

Recursive descent parsing usually refers to hand-written implementations, but there is also a parallel for parser generators — parsing expression grammars, or PEGs for short. The original paper is a good read if you're curious. PEGs correspond pretty directly to recursive descent parsing, so its useful background to have. You can even apply optimizations and such to parsing expression grammars; maybe one-day I'll try to write another optimizing compiler for PEGs… But, I digress. We're going the manual route.

To parse, we must lex

A lexer, or tokenizer, takes the source code and breaks it up into pieces, such as keywords, numbers and symbols. These pieces are called tokens. A parser could operate directly on characters, so this distinction is not strictly necessary, but, in practice, it makes some things easier (e.g. keywords), and can significantly improve performance.

For the moment, we will define the following tokens: CommaToken, SemicolonToken, EqualsToken, IdentToken, IntLiteralToken, KwIntToken, KwReturnToken, OpenBraceToken, CloseBraceToken, OpenParenToken, CloseParenToken, and the special EofToken.

Whenever we reach the end of the source code, we return EofToken, this saves us from having to return null or Optional, which would make the code more complicated.

Our lexer has a fairly simple interface and structure:

public class Lexer {

// The characters that are ignored by the lexer

private static final Set<Character> WHITESPACE =

Set.of(' ', '\t', '\n', '\r');

// Tokens that always match up to the same string

private static final Map<String, Token> SYMBOLS =

Map.of(

"(", new OpenParenToken(),

")", new CloseParenToken(),

"{", new OpenBraceToken(),

"}", new CloseBraceToken(),

";", new SemicolonToken(),

",", new CommaToken(),

"=", new EqualsToken());

// Keywords that should be used instead of an identifier

// where applicable

private static final Map<String, Token> KEYWORDS =

Map.of(

"int", new KwIntToken(),

"return", new KwReturnToken());

// The entire input source code

private final String input;

// The index into the source code we are currently up to

private int position = 0;

public Lexer(String input) {

this.input = input;

}

// Creates a copy of the lexer so we can rewind

public Lexer(Lexer other) {

this.input = other.input;

this.position = other.position;

}

public Token peek() throws LexException {

return new Lexer(this).next();

}

public Token next() throws LexException {

// ...

}

private Token lexSymbol() {

// ...

}

private Token lexWord() {

// ..

}

private Token lexIntLiteral() {

// ..

}

private void skipWhitespace() {

// ..

}

}

The next function does the bulk of the work by delegating to the lex* functions.

The lex* functions either return a token and move position forward, or they return null and leave position as is.

This otherwise isn't too tricky, you just have to make sure you lex int as a keyword, and make sure you don't lex integer as int followed by teger.

Writing the parser

Back to writing the parser. As I mentioned before, recursive descent parsers can often be expressed as parsing expression grammars, which are like an abstract representation of the parsing code, and also have a lot in common with regular expressions. Here is the parsing expression grammar we will be using:

The lefthand side of the 's define a piece of syntax, or a rule, and the righthand side breaks it down into smaller pieces of syntax. The means repeated zero or more times, and the means either the left or right can be chosen. One important quirk, is that we have to list before . Imagine our input was , and we were deciding which expression to match. If we naively tried , we would see that it does indeed match , and then whatever rule is next would fail to parse the remaining . PEGs and recursive descent parsers are not smart enough to handle this automatically, so we must keep track of this ourselves. This might be a bit surprising if you are used to the operator from regular expressions.

Our parser class looks a bit like this. I've omitted most of the code, since it essentially just rehashes the same few patterns, but I've included the tricky bits and a few illustrative examples:

public class Parser {

private Lexer lexer;

public Parser(Lexer lexer) {

this.lexer = lexer;

}

// Each piece of syntax has its own function, and most of

// those functions conform to this interface

private interface ParseFunction<T extends Ast> {

// This attempts to parse out a piece of syntax

// by advancing the lexer. If there is an error

// (e.g. missing semicolon), then we throw an

// exception. Given an error, we might like to

// try to reset/rewind the lexer and try parsing

// something else, but this method is not

// responsible for this resetting/rewinding

T parse(Parser parser) throws ParseException;

}

public static ProgramAst parse(String syntax)

throws ParseException {

return new Parser(new Lexer(syntax)).parse();

}

public ProgramAst parse() throws ParseException {

var ast = parseProgram();

// The `parent` field doesn't get assigned in the

// constructor, so we must fix it up here

ast.assignParents();

return ast;

}

// This is what we will use for parsing individual tokens

private <T extends Token> T expect(Class<T> cls)

throws ParseException {

var next = lexer.peek();

if (!cls.isInstance(next)) {

throw new ParseException(

"expected " + cls + " but found " + next);

}

return (T) lexer.next();

}

// Sometimes we don't want to catch a parsing exception

// and try something else. For example, if we cant parse

// an assignment, maybe we want to parse an integer

// literal instead? This handles catching the exception

// and putting the lexer back in its original state. We

// use this to implement "A / B" rules from the PEG grammar

private <T extends Ast> T attempt(ParseFunction<T> f) {

var copy = new Parser(new Lexer(lexer));

try {

var result = f.parse(copy);

lexer = copy.lexer;

return result;

} catch (ParseException e) {

return null;

}

}

public ProgramAst parseProgram() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private FunctionAst parseFunction() throws ParseException {

var returnTy = parseTy();

var name = parseIdent();

var params = new ArrayList<VarDeclAst>();

expect(OpenParenToken.class);

// This is how we parse "VarDecl (`,` VarDecl)*"

while (!(lexer.peek() instanceof CloseParenToken)) {

if (!params.isEmpty()) {

expect(CommaToken.class);

}

params.add(parseVarDecl());

}

expect(CloseParenToken.class);

var body = parseBlock();

return new FunctionAst(name, params, returnTy, body);

}

private VarDeclAst parseVarDecl() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private TyAst parseTy() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private TyAst parseKwTy() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private BlockAst parseBlock() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private StmtAst parseStmt() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private VarDeclStmtAst parseVarDeclStmt()

throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private ReturnStmtAst parseReturnStmt()

throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private ExprStmtAst parseExprStmt() throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private ExprAst parseExpr() throws ParseException {

// This is how we parse

// "AssignmentExpr / VarExpr / IntLiteralExpr"

AssignmentExprAst assignment =

attempt(Parser::parseAssignmentExpr);

if (assignment != null) return assignment;

VarExprAst variable =

attempt(Parser::parseVariableExpr);

if (variable != null) return variable;

IntLiteralExprAst intLiteral =

attempt(Parser::parseIntLiteralExpr);

if (intLiteral != null) return intLiteral;

throw new ParseException("no valid expression");

}

private VarExprAst parseVariableExpr()

throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private AssignmentExprAst parseAssignmentExpr()

throws ParseException {

// ...

}

private IntLiteralExprAst parseIntLiteralExpr()

throws ParseException {

// ..

}

private IdentAst parseIdent() throws ParseException {

var token = expect(IdentToken.class);

return new IdentAst(token.getContent());

}

}

Neat!

This works well for parsing correct programs into ASTs.

One downside is that this does very poorly in the presence of errors.

For example, trying to parse the statement x = ; will unhelpfully report "no valid statement", and won't tell us where the error occured.

Also, if we have multiple errors, only the first will be reported.

The ability to soldier on in the presence of errors is known as error recovery.

Implementing good error recovery also tends to give us the tools to implement good error reporting, too.

The key to this is having a way to quickly determine which path to go down when chosing between multiple possible branches (e.g. is this an assignment or a variable reference)?

There are several solutions.

One is to make a final decision at each branch by looking at what tokens are ahead.

We can also have each rule "commit" after it knows it is definitely the correct branch.

For example, after seeing the = in an assignment, we know we don't need to backtrack.

This paper gives a good overview of error-handling techniques for PEGs.

The idea of cut-points corresponds loosely to what I'm talking about.

Anyway, implementing this will be left to a later date.

Implementing analysis

We can now happily produce abstract syntax trees from source code. So, for example:

int main(int a, int a) {

return b;

}

Gets correctly turned into this tree:

Although this parsed successfully, there is still an error: int a is defined twice, and b is defined nowhere!

We have validated the syntax of the program, but we still need to validate the sematics.

This is best implemented as several passes that run over the AST and detects all errors of a certain class.

The visitor API

Walking over ASTs can be painful since we usually only care about a few nodes. For example, when we are reporting duplicate identifiers, we don't care about integer literals. To simplify this logic, we use the visitor pattern. Our visitor class will look like this:

public interface AstVisitor {

private void visitChildren(Ast node)

throws AnalysisException {

for (var child : node.getChildren()) {

child.accept(this);

}

}

default void visitProgram(ProgramAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

visitChildren(ast);

}

default void visitFunction(FunctionAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

visitChildren(ast);

}

default void visitVarDecl(VarDeclAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

visitChildren(ast);

}

// Etc...

}

To supplement this, we will have a new method on Ast:

public abstract sealed class Ast

permits /* ... */ {

// ...

public abstract void accept(AstVisitor visitor)

throws AnalysisException;

}

Implementations of accept just delegate to the appropriate visit* method, so ProgramAst::accept calls AstVisitor::visitProgram, and so on.

The default implemention of all the visit* methods just visits all the children in order.

Generally we will override some of these methods, but still call the super-implementation to continue visiting the rest of the AST below the current node.

Collecting names

Our first analysis pass will scan through all function and variable declarations, and make sure there are no duplicates. We will also take the opportunity to store away all these declarations for future passes. This pass does not modify the AST in any way, it just validates the AST and stores information for later. The code looks a bit like this:

public class CollectNames implements AstVisitor {

private Map<IdentAst, FunctionAst> functions

= new HashMap<>();

private Map<NameInFunction, VarDeclAst> variables

= new HashMap<>();

private record NameInFunction(IdentAst function,

IdentAst variable) {}

public FunctionAst getFunction(IdentAst ident) {

return functions.get(ident);

}

public VarDeclAst getVariable(IdentAst function,

IdentAst ident) {

return variables.get(new NameInFunction(function, ident));

}

@Override

public void visitFunction(FunctionAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

var functionName = ast.getName();

if (functions.put(functionName, ast) != null) {

throw new AnalysisException(

"function " + functionName + " already exists");

}

AstVisitor.super.visitFunction(ast);

}

@Override

public void visitVarDecl(VarDeclAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

var function = ast.findAncestor(FunctionAst.class);

var nameInFunction = new NameInFunction(

function.getName(), ast.getName());

if (variables.put(nameInFunction, ast) != null) {

throw new AnalysisException(

"variable " + ast.getName() + " already exists");

}

AstVisitor.super.visitVarDecl(ast);

}

}

Resolving names

We will implement one more pass, that makes sure all referenced names are defined.

This will depend on the results from the CollectNames pass, so will take it as a constructor parameter.

Since it is helpful for the usage of a variable or function to link directly to the corresponding declaration, we'll use this pass to insert those links into the AST.

Most of our analysis passes won't significantly edit the AST, but some will fill in missing information, like these declaration links.

Here is the code for name resolution:

public class ResolveNames implements AstVisitor {

private final CollectNames collected;

public ResolveNames(CollectNames collected) {

this.collected = collected;

}

@Override

public void visitAssignmentExpr(AssignmentExprAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

var function = ast.findAncestor(FunctionAst.class);

var decl = collected.getVariable(

function.getName(), ast.getVariable());

if (decl == null) {

throw new AnalysisException(

"use of undeclared variable " + ast.getVariable());

}

ast.setDecl(decl);

AstVisitor.super.visitAssignmentExpr(ast);

}

@Override

public void visitVariableExpr(VarExprAst ast)

throws AnalysisException {

var function = ast.findAncestor(FunctionAst.class);

var decl = collected.getVariable(

function.getName(), ast.getName());

if (decl == null) {

throw new AnalysisException(

"use of undeclared variable " + ast.getName());

}

ast.setDecl(decl);

AstVisitor.super.visitVariableExpr(ast);

}

}

A trivial interpreter

I promised to write a compiler — and I will — but I'm going to mostly leave it here for now. But before I go, I'm going to write a very basic interpreter for our ASTs. I'm throwing this in mostly because its just so easy, but its also super helpful for debugging. There are of course fancy techniques for interpreters, but I'm just going to write a very simple AST-walking interpreter, which works exactly how it sounds. The code is pretty simple, although I've omitted some error-handling:

public class Interpreter {

private final ProgramAst ast;

// When a function is called, a stack-frame holds all the local

// variables. We store the stack frames as maps in a stack

private Deque<Map<IdentAst, Value>> stack = new ArrayDeque<>();

public Interpreter(ProgramAst ast) {

this.ast = ast;

}

private Value runFunction(FunctionAst ast, List<Value> args)

throws InterpretException {

var variables = new HashMap<IdentAst, Value>();

stack.push(variables);

// Copy over any paramters

for (var i = 0; i < args.size(); i++) {

var param = ast.getParams().get(i);

var value = args.get(i);

variables.put(param.getName(), value);

}

try {

return runBlock(ast.getBody());

} finally {

stack.pop();

}

}

private Value runBlock(BlockAst ast)

throws InterpretException {

for (var stmt : ast.getStmts()) {

switch (stmt) {

case VarDeclStmtAst ignored -> {}

case ReturnStmtAst returnStmt -> {

return evalExpr(returnStmt.getValue());

}

case ExprStmtAst exprStmt ->

evalExpr(exprStmt.getExpr());

}

}

throw new InterpretException("function did not return");

}

private Value evalExpr(ExprAst ast) throws InterpretException {

return switch (ast) {

case VarExprAst variable ->

stack.peek().get(variable.getName());

case IntLiteralExprAst intLiteral ->

new IntValue(intLiteral.getValue());

case AssignmentExprAst assignment -> {

var value = evalExpr(assignment.getValue());

stack.peek().put(assignment.getVariable(), value);

yield value;

}

};

}

}

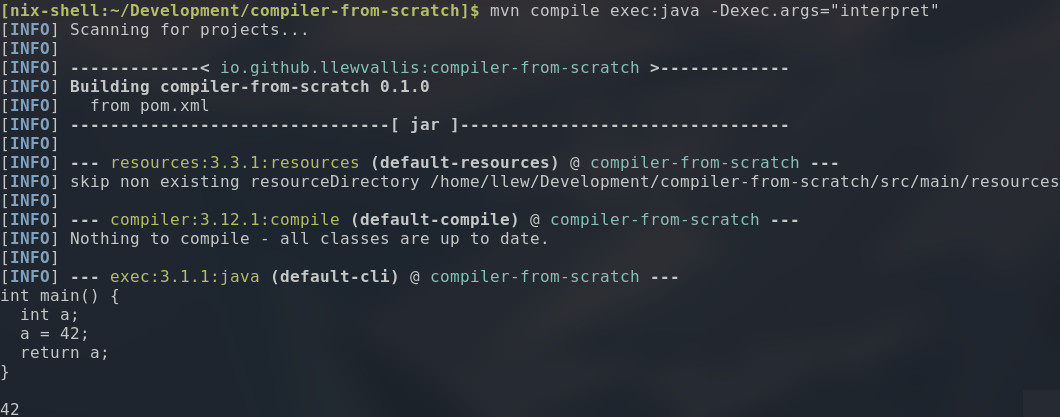

This works pretty well. I won't show the code here, but I've also written somes tests and a very basic CLI interface to make the compiler nicer to work with. So for example we can do:

Check out the code

If you want to play around, or peek into the details, you can check out the code for this chapter here, or the master branch here.

Footnotes

-

Very cool slides from Graydon Hoare, creator of Rust. Well worth a look. ↩

-

LLVM (and Clang) use a representation based on instructions, basic blocks, and single static assignment form. This is a terrific resource introducing LLVM IR. ↩

-

The V8 JavaScript engine is based on a sea of nodes representation. There is a good blog post explaining it more. ↩

-

Despite this the pervasive Tree-sitter project, which appears in many IDEs and powers GitHub's syntax highlighting, is a bottom-up parser. Tree sitter is incremental, so small edits to the source can be handled efficiently, but there are also simple incremental methods for PEG parsing. ↩